In “Advanced Readings in D&D,” Tor.com writers Tim Callahan and Mordicai Knode take a look at Gary Gygax’s favorite authors and reread one per week, in an effort to explore the origins of Dungeons & Dragons and see which of these sometimes-famous, sometimes-obscure authors are worth rereading today. Sometimes the posts will be conversations, while other times they will be solo reflections, but one thing is guaranteed: Appendix N will be written about, along with dungeons, and maybe dragons, and probably wizards, and sometimes robots, and, if you’re up for it, even more.

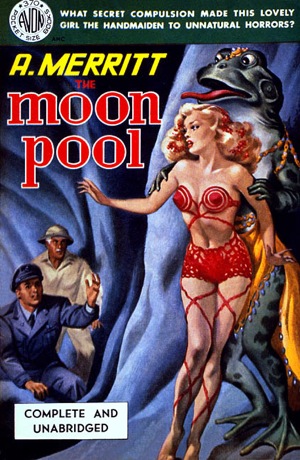

Up this week is A. Merritt’s The Moon Pool, full of ray guns, frogmen and lost civilizations!

Tim Callahan: I don’t know which edition of A. Merritt’s The Moon Pool you ended up buying, but the version I have is a sad attempt to cash in on the popularity of ABC’s Lost. How can I tell? Because the front and back cover mention Lost no less than SEVEN times. I’m paraphrasing with this not-quite-real-cover-copy, but this ugly edition of The Moon Pool is sold as “If you like Lost, you’ll like this lost classic about a lost civilization that inspired the TV show Lost!”

But here’s the problem, besides the cash-grab grotesquerie of the cover: The Moon Pool is nothing like Lost. It has about as much to do with Lost as The Jetsons has to do with Star Wars. And The Moon Pool has more imagination in any one chapter than Lost had in any ultra-long and tedious season.

This conversation about A. Merritt and The Moon Pool has already gotten away from me and revealed my longstanding animosity toward a supremely disappointing show that I watched every single episode of. The Moon Pool deserves better.

Mordicai Knode: I got an old used copy but I can see why some enterprising editor would try to rebrand it. It does have a mysterious island! And Lost was a big cultural phenomenon for a minute there…but yeah, no. It is like comparing Mega Shark Versus Crocosaurus to Alien or The Thing. Sure, they all have monsters, but… (Also, I think Lost and Mega Shark Versus Crocosaurus have their place, but like you said, that place is not “compared to a masterwork.”)

Can I just say what a sucker I am for “found documents” stories? I know it is an easy trick, but it works on me every time—just toss in a little frame story wherein someone says “oh, the mad professor was never found, but this is his diary!” But The Moon Pool starts out with a double framestory, with the mad scientist confessing his story to his confederate plus a letter from the President of the International Association of Science testifying to its veracity, saying that it has been novelized for the layman. Laying it on thick but like I said, that hits the sweet spot for me, I’m all about it.

One more thing, before we actually start talking about the book. I have had night terrors and sleep paralysis before, and I couldn’t help but think of that when Merritt was talking about everyone’s sudden narcolepsy at the door of the Moon Cave. The hypnagogic terror struck home in a way that made me wonder about the author’s own sleep history. In the same vein, we were talking about H.P. Lovecraft before; his creations the nightgaunts are faceless flying monsters that…tickle your toes. It sounds, on the face of it, absurd—but to me it sounds horrifying, and makes me convinced that old Howard Phillip suffered the same malady.

TC: The frightening unreality of dream—and the line between dream and imagination and wakefulness and reality—that’s the stuff that’s clearly in play with The Moon Pool. I’d be surprised if Merritt didn’t pull from his own personal experiences with terrors of the sort you’re talking about, particularly early in the book when the unreality of the island and the portal into the bizarre world seems so eerie and unsettling.

It’s one of the aspects of the novel I like best: the trope of the passage to another realm filled with strange creatures and a mystical civilization is so banal in fantasy fiction and role-playing game adventures that it’s often presented like just going to a strange bus stop or something. But Merritt really pushes the weirdness of the experience, and when he wrote this book, it wasn’t as much of a cliche as it is now. But even now, if it happened in real life next time you were on vacation to a tropical island, it would be absolutely horrific. We wouldn’t even be able to process what we were seeing if we really had this kind of contact with green dwarfs and nameless tentacle creatures and underground princesses.

Speaking of all that stuff, were you able to make sense out of the mythology in The Moon Pool. Can you map out the relationship between the Dweller and the Three and the Shining One? Because I will admit that I lost track of the hierarchy of supernatural beings by the time I got to the last third of the novel. I felt like I needed to go back and diagram it out, but maybe I just missed the key to the pantheon somewhere along the way.

MK: Oh yeah, the novel can be a little gloriously unclear. It is sort of your basic John Carter of Mars tale of white guys in an alien land, but filtered through some Dunsany-like prose, just florid as get-out. It made me really long for the academic footnotes. Anyhow, here is how I think it played out. On the proto-Earth—or well in the center of it, anyhow—the Tuatha de Danaan-esque Taithu evolve. Bird-lizard-angel-people. Three of them are like the cream of the crop, and they create the Shining One, because they see life evolving on the surface and they want a toy of their own to play with. The Shining One is a tool that surpasses its makers—basically their artificial intelligence that eclipses them. During all of this, maybe during the age of dinosaurs, some frog-apes find their way into the cavern, and they are allowed to live there, until they evolve into the sentient frog-people of the Akka. The rest of the Taithu sort of disappear—maybe actually to actual Ireland—while the tensions between the Silent Ones and the Shining One mount. Eventually, they make contact with the surface of the Earth, where humans finally exist. There is a caste system—most people have dark hair, but blonde people are moon cultists and red haired people are sun cultists. They are brought into the hollow of the Earth and their breeding patterns create the three sub-races of humans.

Wow that is…listen, that sounds like a lot of exposition but it isn’t needed, because like Tim says, the book really capitalizes on the feeling of the alien. This isn’t some dungeon of ten by ten stone hallways. This is a whole weird social system, internally consistent but not consistently revealed. You know what it really reminds me of? The classic adventure, The Lost City (Module B4). Weird costumes, masks, drugs, the whole thing, all topped off with a strange monster ruling it all. I had a ton of fun playing that adventure.

TC: I am still playing that adventure. I ran The Lost City as a solo adventure for my son when he first started playing, and when a bunch of kids wanted me to run an adventure for them after school this year, I kicked off an expanded version of The Lost City for them—more underground city crawl and warring factions and the psychedelic weirdness of the Cult of Zargon than the meandering around the temple passageways. I love that module the most, mainly because it gives the players a great starting point and offers a lot of possibilities for adding depth and substance and…well, you could run an entire campaign beneath that buried temple.

Your explication of the Moon Pool mythology makes sense to me, given what I was able to piece together as I read the book, but i definitely didn’t get that much out of the way Merritt crafted the mythology in the prose. But I suppose that’s kind of the point—that the mechanics of the unknown aren’t as important as the way the characters interact with the unknown—and there’s something wonderful about how far Merritt goes with his underground cosmology even though none of it really matters in a story sense. But it adds a crazy wall of texture to provide more than just background for the adventure. It provides an entire unsettling context.

Really, though, the whole thing is totally a dungeon crawl with odd NPCs and surprises and even a love story of the type you might find in a classic D&D adventure where one of the characters falls for the daughter of the alien king.

Moon Pool feels like an ur-text for Dungeons and Dragons, more than most of the books in Appendix N. It’s even full of bad accents!

MK: Okay, so we both liked this book, but lets put on the brakes for a minute—this book is part of the same misogynistic and racist context as a lot of the other books we’ve read. The big difference is that it is fun, but that shouldn’t keep us from being critical about it. So let’s knock that out a little bit. First: the Madonna/Whore dichotomy could not be clearer. I mean, wow. While the two women of the story—apart from a few sex slaves, which, ew—make a lot of noises about being dangerous, with their ray guns and poisonous flowers, in the clutch of things they are, you know, overcome by raw masculine energy or some such rot. Not to mention the usual swath of civilized white people, savage brown people, and magical super white people. Not a fan of that, either. Still, I think you can be critical of something you like; in fact I would say it is crucial to be critical of things you like!

TC: Moon Pool is just as misogynist and racist as almost all the other sci-fi romances of the first half of the 20th century, sure. And that’s the problem. That I can just wave my hand and say, “well, it’s just like everything else” and kind of ignore those problems because they are endemic to the genre at that time in history. But, at the same time, I don’t know that we can do much more than point it out and say, “that’s wrong.” Well, I suppose we could do more, but I don’t think this is the forum for it. Part of me thinks that we should just provide a blanket statement that addresses the fact that most of these books in Appendix N are problematic in their portrayals of race and gender and act as white male power fantasies more often than not, but by offering such a statement, the implication is that, “yeah, yeah, we know this stuff’s corrupt at a moral level, at its depictions of actual humans, but we’re going to mostly ignore that because, hey, rayguns and underground cities and monsters!”

In other words, I’m conflicted, but I’m easily distracted by rayguns and underground cities and monsters.

Tim Callahan usually writes about comics and Mordicai Knode usually writes about games. They both play a lot of Dungeons & Dragons.

MOON DWARVES.

Inadvertent post, please delete.

@mordicai & Callahan: Thought you would enjoy this one. Merritt had a strong influence on H. P. but Lovecraft never liked the novel version of The Moon Pool (he preferred the equally pulpy sequel, The Metal Monster). It’s fairly obvious why: Merritt’s imagination could, at best, transcend weaknesses in style and plot. Plenty of authors had a Merritt stage, perhaps most notably Jack Williamson. Also, Tim Powers contributed an introduction to the Planet Stories reissue of The Ship of Ishtar.

EDIT: Double post. I’ll just note that “The Call of Cthulhu” is considered to be Lovecraft’s “Merritt” story.

Yeah, Merritt has a lot of… um… merits. A very good writer all in all, though he does rely a little heavily on the lost civilization trope. And there, what he’s really drawing on is primarily Rider Haggard (doing the mysticism better, however).

I think his best contribution to the education of the young DM is that ability to give you enough information to get on with, while not going into excessive detail. And if you’re a little confused by some of it, it’s still told well enough for you to go on with the story and not worry about some of the details.

Never read any of Merritt’s novels, this one sounds kind of interesting. The next time I am at The Book Barn (my favorite used bookstore, in Niantic, CT), I will look for this one.

3. SchuylerH

Ha ha ha that is an awesome way of putting it.

4. DemetriosX

Yeah, play to the hook; you want the reader– or the player– to have just enough info for their own imagination to do some of the heavy lifting!

5. AlanBrown

Just look for the LOST sticker!

On a personal note, since we mentioned Zargon: in a campaign I was in, my goblin sniper totally killed Zargon– I was swallowed whole & had a helm of brilliance; I hit him with prismatic spray from the inside– & the horn kept regenerating, so I had to keep it in stasis in a bad of holding. Also I usurped his attempts to become a god to, you know, become a god myself. Ah, that was a good campaign; half Planescape, half Spelljammer.

I haven’t read The Moon Pool (I haven’t been able to find a copy), but I have read The Face in the Abyss and have two of his other books are sitting on my bookshelf (Dwellers in the Mirage and The Ship of Ishtar). I think that A. Merritt and Sterling Lanier are the two “hidden gems” of Appendix N, and it’s hard to believe that someone who was that popular, influential, and well-compensated could be all but forgotten today.

Once I got used to Merritt’s prose style (it took about 25 pages), I found him to be a rollicking good read. That’s some real adventure writing there what with dinosaurs, lost cities, mutants, ancient technology that’s all but magic, and some seriously creepy shit. I loved it and can’t wait to read more of his work.

Dwellers in the Mirage is the most “Gygaxian” novel I have ever read (including Gygax’s own Sea of Death). The prose is gloriously purple and the action suitable outré. The novel also subverts the “racialist” subtext of most of its pulp contemporaries- the villains are proto-Aryan holdouts in a (you got it) lost world, while the admitedly Aryan-type protagonist is aided by Cherokee-speaking “little people”.

The “Elder Elemental God” in G3 is a direct steal from the evil “god” in the novel.

The Face in the Abyss is another great read, with the hero falling in love with the princess of a (you got it) lost world, and aiding some (this is a trope-subverter) benevolent spider-people and a wise snake queen. There’s also an evil godlike being imprisoned in a mosaic which cries golden tears… it’s very trippy.

@6: I’ve noticed that you tend to give a positive reception to the really pulpy stuff: Gardner Fox, Lin Carter, Edgar Rice Burroughs and now Merritt. I wonder what you will make of Philip José Farmer?

@8: The Moon Pool is, I think, available as a free ebook on Project Gutenberg. The Ship of Ishtar is probably my favorite Merritt, mostly due to the Babylonian setting.

Just a bit of Lovecraftiana I’ve found: Merritt, Frank Belknap Long, C. L. Moore, H. P. Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard wrote a round-robin style story for Fantasy Magazine, “The Challenge from Beyond”. The same issue included a less well-known story of the same title, this time SF, written by Stanley G. Weinbaum, Donald Wandrei, “Doc” Smith, Harl Vincent and Murray Leinster.

It should also be noted that Merritt was a rather prominent editor for the Sunday supplement The American Weekly. He was the first person to hire both Virgil Finlay and Hannes Bok, both of whom had a lot of influence on D&D art.

8. Tim_Eagon

I’d add Weinbaum to that list, only maybe people don’t think he’s hidden? Hidden from me, anyhow.

9. Kirth Girthsome

…hold up, spider people are my scene! Those both sound really awesome.

10. SchuylerH

Farmer should be next week…

12. DemetriosX

Before I started working in publishing, I was rather ignorant about editors & the size of their role, especially in fledgling genres; I’m always happy to give them their due, now, to make up for that!

13. mordicai

I haven’t had a chance to read Weinbaum yet, but I did manage to locate a copy of A Martian Odyssey at a local used bookstore; now I just need to find the time to stop and pick it up. Also, the spider people in The Face in the Abyss are truly awesome; in addition, the first part of that book serves as the inspiration for Fraz-Urb’luu’s imprisonment in Castle Greyhawk, and Merritt’s description of Nimir’s vile gardens are some of the creepiest passages I’ve ever read. Did I mention all the dinosaurs and the huge science-fantasy battle?

9. Kirth Girthsome

I was going to point out that while Merritt’s works are problematic by today’s standards, there’s a lot of nuance to his work (especially when you compare it to other contemporary works in the lost world genre). For instance, in The Face in the Abyss, the Snake Mother may spout lots of tired cliches about the differences between the sexes, but she’s both the most powerful and interesting character in the book (OK, Nimir is actually the most interesting IMO, but she’s a close second). No one trifles with the Snake Mother, least of all the evil white people – both European/American and Yu-Atalanchi -running around.

14. Tim_Eagon

Spider-people, dinosaurs, creepy gardens…now if there was a crashed spaceship, it would sound exactly like one of my campaigns!

15. mordicai

There’s not a spaceship, but there’s a lot of quasi-magical high technology (we’re talking Clarke’s 3rd law here for sure).

I recently downloaded and read this one. It looks like an influence on Karl Edward Wagner; quite a bit of the imagery in Bloodstone seems derived from it, together with Wagner’s fondness for the word “batrachian”! There seem to be different versions; the text I downloaded from Project Gutenberg has an evil Russian character named Marakinoff, whereas the one from Archive.org has an evil German character called Von Hetzdorp.